Aphakia is the absence of the natural crystalline lens in the eye. In children, it may be the result of surgical intervention for congenital or acquired cataract or ectopia lentis, which is the subluxation of the natural crystalline lens due to weakened or lost zonular support. If left aphakic without intervention, children are highly predisposed to deprivation amblyopia, necessitating early and effective visual rehabilitation20. Current treatment options are aphakic contact lenses, glasses or intraocular lenses (IOLs). The leading treatment option for children over the age of two is implantation of an intraocular lens (IOL) in the capsular bag after lensectomy27. However, certain complications of surgery or trauma can compromise the capsular support and preclude usage of a traditional posterior chamber IOL. There are a number of accepted techniques and lens types that can manage this condition in adults, but for children, there is a gap in viable treatment options. The ARTISAN® Aphakia IOL for anterior chamber iris fixation, long the backup lens of choice in Europe and Asia for adults, is currently under clinical investigation as a potential treatment to serve this patient population.

Children may be born with cataracts or acquire them, usually from trauma, either blunt or perforating. Trauma can also cause ectopia lentis, although it may be spontaneous or arise as a complication of certain genetic disorders of connective tissue metabolism, such as Marfan’s, Homocystinuria, or Weill-Marchesani’s. Depending on severity, ectopia lentis may be asymptomatic or cause significant and progressive myopia, diplopia, amblyopia and glaucoma8. Further complications can result if the lens dislocates into the vitreous or the anterior chamber. Dislocation into the anterior chamber can cause angle closure glaucoma, pupillary block, damage to the corneal endothelium, and retinal detachment20. Early detection and removal of the cataract or dislocated lens not only prevents complications but also improves the outcome for visual rehabilitation, as younger eyes have higher risk of amblyopia and sensory nystagmus17.

The prescribed treatment for cataracts and severely dislocated lenses in children is surgical removal of the lens via phacoemulsification techniques or pars plana lensectomy with a goal of leaving the lens capsule intact. It is often coupled with anterior vitrectomy to prevent secondary complications20.

The resulting aphakia has several treatment options that are influenced by the age of the child. After removal of infantile cataract, many doctors prefer to leave a child aphakic before the age of two, with conservative treatment through aphakic contact lenses and spectacles. Aphakic contact lenses are effective with proper compliance, best achieved with education of parents in the importance of consistent usage, though children may be intolerant. Aphakic spectacles are cumbersome and cosmetically unsatisfactory, affecting patient quality of life; their limited visual field (i.e. “jack-in-the-box effect”) is unfavorable; and their usage is unsuitable with unilateral aphakia due to the risk of aniseikonia, which interferes with the development of binocular function1,19,21. Poor compliance with aphakic contacts and spectacles increases the risk of amblyopia and poor vision.

Compliance issues can be circumvented by the implantation of an IOL, and IOL usage in children over the age of two is becoming more accepted, especially as evidence of long-term safety in adults accumulates. IOL usage before the age of two is avoided because the smaller eyes of children present a greater risk of complications with IOLs, such as posterior chamber opacification and uveitis; as the eye grows rapidly, the larger size can result in IOL decentration or IOL rotation, which for anterior chamber lenses carries a greater risk of endothelial cell loss (ECL)21,8. Posterior chamber IOLs placed in the bag has become routine in treatment of pediatric cataract but requires a lens capsule with sufficient zonular support28,31. Complicated cataract surgery may and severe ectopia lentis does compromise the capsular bag, leaving no such support. Mild zonular dehiscence of less than a quadrant can potentially be stabilized with a capsular tension ring and has been reported with success in children4,29, but severe cases require different treatment.

There are many techniques that attempt to still utilize the traditional three-piece posterior chamber IOL but innovate a new means for securing the haptics via glue or sutures24, or more recently flanged haptic tips as in the Yamane technique33. These techniques rely on surgically placing tunnels through the sclera of the eye 180 degrees apart on a parallel plane of the iris, then pulling through the haptics of a three-piece IOL to be captured and buried within the scleral tissue. To ensure stable fixation, the haptics can be glued with fibrin glue, tied to the sclera with prolene sutures, or have their tips melted into a flange that prevents haptic erosion into the sclera. The tunnel entries are then sealed under scleral flaps. Sutures may also be used to fixate to iris tissue instead of sclera, which is technically less demanding16,24.

These techniques have had success in adult eyes, yet the sclera of children is elastic and still developing and it is uncertain how safe these techniques are in children. Scleral flaps tend to atrophy with time, exposing the original tunnel, which can be an entry point for bacteria, increasing the risk of endophthalmitis21,24. Sutured IOLs, whether transscleral or iris fixated, have a risk of suture degradation as the polypropylene sutures destabilize in the body over time, causing IOL tilt, decentration or subluxation21,24-26. Due to the long-projected life span of the patient population, the risk of degradation of sutures and resultant dislocation of sutured IOLs discourages usage in children26,31,34-35. For these reasons, doctors are cautious to use these fixation techniques in children.

Another type of back-up lens is the anterior chamber IOL. Angle supported IOLs and the iris claw IOLs are two anterior chamber lens designs used in adults lacking capsular support. It is reported that anterior chamber lenses carry an increased risk of accelerated endothelial cell density loss as the proximity of the lens to the cornea may influence the decline of endothelial cells, which do not regenerate mitotically21,29. It is therefore important to have long term follow up monitoring the endothelial cell count.

Angle supported IOLs have haptics that loop outward from the optic and foot plates that extend into the angle of the anterior chamber, where they support the lens. The angle of the eye is the drainage site for aqueous humor, and this flow is potentially blocked by the lens haptics, which can cause corneal edema and angle-closure glaucoma14,24. If poorly sized, the haptics can also bury into the tissue of the angle recess or ciliary body over time, in what is called a “cheese cutter” fashion24. Additionally, angle supported anterior chamber IOLs pose a challenge for correct sizing in the growing eyes of children; even well-positioned angle supported anterior chamber IOL will begin to rotate after the eye grows larger3.

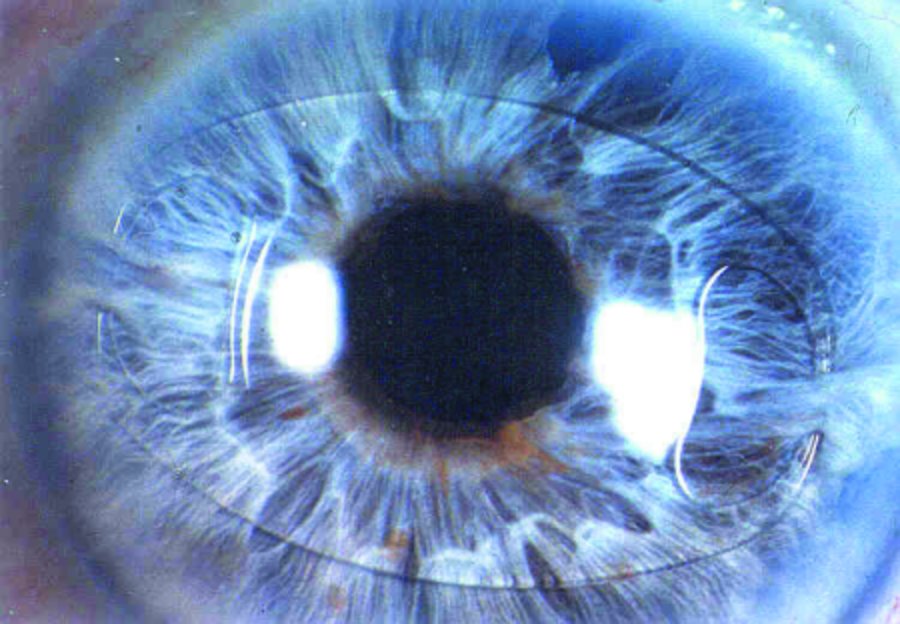

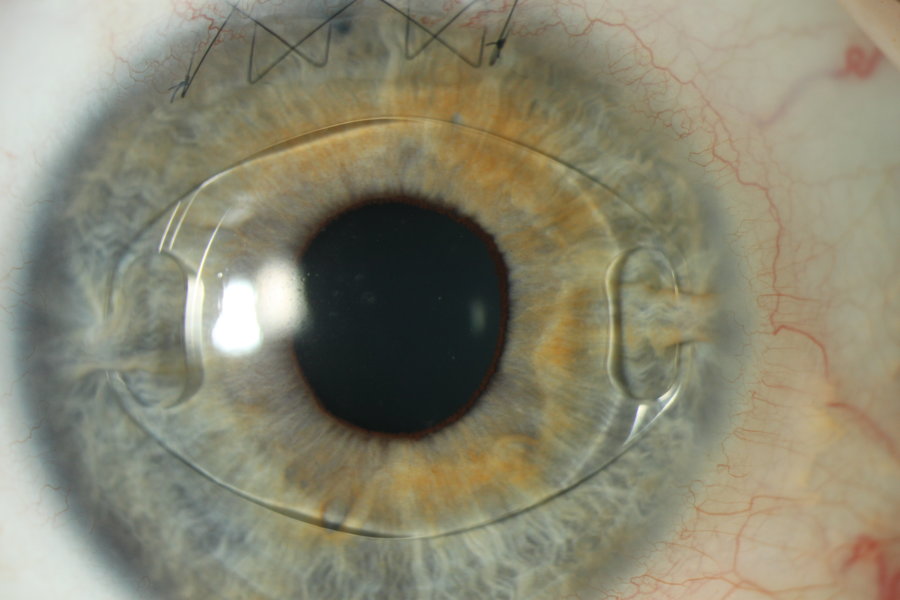

The iris claw IOL is not currently FDA approved, though it has a long history of usage with acceptable rates of complications found in the literature for adults and off label for children in Europe and Asia; those found in this bibliography are a short survey3,5-13,15-16,18,24,26,31. The lens is currently under clinical investigation in the United States. Developed in 1978, the iris claw IOL is the invention of Prof. Jan Worst, who serendipitously discovered iris tissue was unaffected when captured within the haptic claws of a previous version of the iris fixated lenses he had designed for the correction of aphakia. Called the ARTISAN® Aphakia, the IOL is a single piece PMMA lens, coming in one size with an overall diameter of 8.5 mm, a 5 mm optic and two iridoplastic bridges or “claws” diametrically placed on each side. These claws have a slot that allow for a small tuft of iris tissue to be picked up from the relatively immobile anterior mid-periphery of the iris stroma and remain captured between them through a technique called enclavation. With proper technique, the IOL should remain stably fixated, ensuring no post-operative rotation and maintaining centration over the pupil23.

Children who experience blunt force trauma to the eye have a high risk of experiencing IOL dislocation2-3,5,10-11,25. Usually, only one haptic disenclavates and repositioning and reenclavation is the next step, though explantation can sometimes be required if the haptic has deformation or damage. Spontaneous IOL dislocation has been reported in several patients6,9,22, and when it occurs, it may be the result of insufficient enclavation of iris tissue. Insufficient enclavation of iris tissue leading to IOL luxation is most often observed at the beginning of the learning curve of the implantation procedure2,9,11, and it has been suggested that inadequate tissue support may be an influence in patients with certain hereditary disorders6. Overall, the literature suggests that for most patients, long term stable fixation is the result.

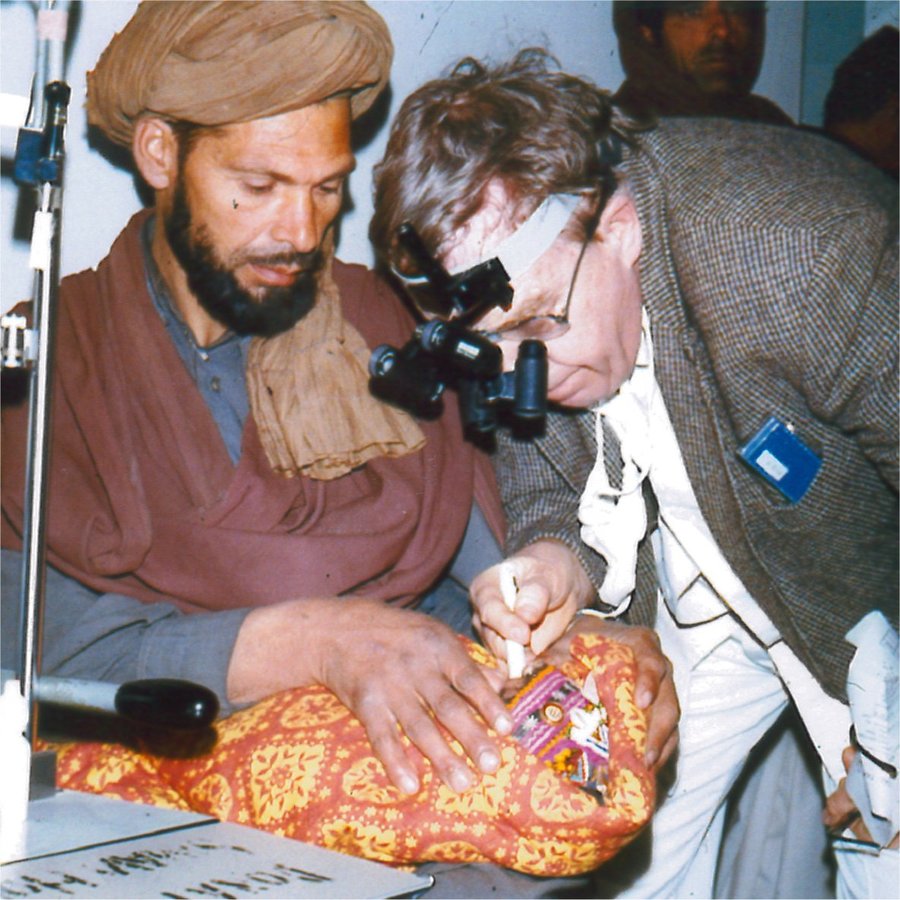

The limited viable treatment options for pediatric patients with absence of capsule support and the long history of safe usage in Europe and Asia warrant the current investigation of the of the ARTISAN® Aphakia IOL to bring the lens into the United States. The current investigation is a multi-center, open label study sponsored by Ophtec, the manufacturer of the lens. Pediatric patients are followed on a prescribed schedule of 10 visits over the course of 5 years to determine the effectiveness of the lens in the treatment of aphakia and to precisely define the associated risks.

The targeted end point for Best Corrected Distance Visual Acuity (BCDVA) is an improvement of one or more lines of HOTV, LEA or Snellen test for at least 85% of the subjects at 12 months post-operative. Additionally, no more than 5% of the subjects should experience a reduction of more than 2 lines in BCDVA23. In comparison to previously discussed posterior chamber lens fixation techniques, studies in adults show that the ARTISAN® Aphakia IOL has comparable improvement to BCDVA and the advantages of significantly shorter surgical procedure and a faster time for visual recovery from less surgical trauma9,13,15,25. Studies of pediatric usage also show a significant improvement of visual acuity if conditions, such as severe corneal scarring due to trauma, intractable amblyopia or retinal detachment, are not concurrent3,5-8,10-11,16,18,27,32.

A common limitation of pediatric ARTISAN® studies in the literature is small sample size as the patient population that qualify for ARTISAN® Aphakia is limited. The current trial seeks to follow 300 patients over 5 years, with enrollment still active and an expected closing date in 2021. To qualify for the study, patients must be between the ages of 2 and 21, have no iris, corneal or retinal abnormalities that would preclude visual improvement or successful enclavation nor have any incidence or history of retinal detachment, glaucoma or uveitis. Currently, 17 active investigators across the US have successfully implanted 295 eyes in 171 patients.

Dr. M. Edward Wilson, Professor of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics of the Albert Florens Storm Eye Institute and Medical University of South Carolina, is an active investigator who offers this comment, “I had been asking for this protocol for years. The ARTISAN® IOL has a proven track record for children worldwide. It gives surgeons a ‘one size fits all’ IOL in a growing eye, and it has been shown to be stable and well tolerated by the growing eye for many years”30. If endpoints for safety and efficacy are met, aphakic children lacking capsular support will have another viable treatment option more widely available in the US.

References

- Alireza, B., Ebrahim, S., Medi, E., & Mitra, A. (2014). Optical Correction of Aphakia in Children. Journal Of Ophthalmic & Vision Research, Vol 9, Iss 1, Pp 71-82 (2014), (1), 71.

- Barbara, R., Rufai, S. R., Tan, N., & Self, J. E. (2016). Is an iris claw IOL a good option for correcting surgically induced aphakia in children? A review of the literature and illustrative case study. Eye, 30(9), 1155-1159. doi:10.1038/eye.2016.140

- Brandner M, Thaler-Saliba S, Plainer S, Vidic B, El-Shabrawi Y, Ardjomand N (2015). Retropupillary Fixation of Iris-Claw Intraocular Lens for Aphakic Eyes in Children. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0126614. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126614

- Byrd J, Young M, Owen L, et al. Article: Long-term outcomes for pediatric patients having transscleral fixation of the capsular bag with intraocular lens for ectopia lentis. Journal Of Cataract & Refractive Surgery [serial online]. May 1, 2018;44:603-609.

- Català-Mora, J., Cuadras, D., Díaz-Cascajosa, J., Castany-Aregall, M., Prat-Bartomeu, J., & García-Arumí, J. (2016). Anterior iris-claw intraocular lens implantation for the management of nontraumatic ectopia lentis: Long-term outcomes in a paediatric cohort. Acta Ophthalmologica, 95(2), 170-174. doi:10.1111/aos.13192

- Çevik, S. G., Çevik, M. Ö, & Özmen, A. T. (2017). Iris-claw intraocular lens implantation in children with ectopia lentis. Arquivos Brasileiros De Oftalmologia, 80(2), 114-117. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20170027

- Cleary, C., Lanigan, B., O’Keefe, M. (2012). ARTISAN® iris-claw lenses for the correction of aphakia in children following lensectomy for ectopia lentis. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 96(3): 419-421.

- Faria, M., Ferreira, N., & Neto, E. (2016). Retropupillary iris-claw intraocular lens in ectopia lentis in Marfan syndrome. International Medical Case Reports Journal, 9, 149-153. doi:10.2147/imcrj.s106382

- Fereydoun, F., Mostafa, F., Foad, H., et al. (2012). Iris Claw versus Scleral Fixation Intraocular Lens Implantation during Pars Plana Vitrectomy. Journal Of Ophthalmic & Vision Research, Vol 7, Iss 2, Pp 118-124 (2012), (2), 118.

- Gawdat, G.I., Taher, S.G., Salama, M.M., Ali, A.A. (2015). Evaluation of ARTISAN® aphakic intraocular lens in cases of pediatric aphakia with insufficient capsular support. Journal of AAPOS, 19(3): 242-246.

- Gonnermann, J., Torun, N., Klamann, M. K., Maier, A., Sonnleithner, C. V., Rieck, P. W., & Bertelmann, E. (2013). Posterior Iris-claw Aphakic Intraocular Lens Implantation in Children. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 156(2), 382-386. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2013.03.002

- Guell, JL., Verdaguer, P., Elies, D., et al. (2014) Secondary iris-claw anterior chamber lens implantation in patients with aphakia without capsular support. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 98(5):658-63.

- Hara, S., Borkenstein, A. F., Ehmer, A., & Auffarth, G. U. (2011). Retropupillary Fixation of Iris-claw Intraocular Lens Versus Transscleral Suturing Fixation for Aphakic Eyes Without Capsular Support. Journal of Refractive Surgery, 27(10), 729-735. doi:10.3928/1081597x-20110623-01

- Hayashi, K., Hirata, A., & Hayashi, H. (2011). In-the-bag scleral suturing of intraocular lens in eyes with severe zonular dehiscence. Eye, 26(1), 88-95. doi:10.1038/eye.2011.242

- He, T., & Hong, Z. (2014). Comparison of Artisan iris-claw intraocular lens implantation and posterior chamber intraocular lens sulcus fixation for aphakic eyes. International Journal Of Ophthalmology, Vol 7, Iss 2, Pp 283-287 (2014), (2), 283. doi:10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.02.16

- Hirashima, D. E., Soriano, E. S., Meirelles, R. L., Alberti, G. N., & Nosé, W. (2010). Outcomes of Iris-Claw Anterior Chamber versus Iris-Fixated Foldable Intraocular Lens in Subluxated Lens Secondary to Marfan Syndrome. Ophthalmology, 117(8), 1479-1485. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.043

- Lambert, S.R., Lynn, M.J., Reeves, R. et al. (2006). Is there a latent period for the surgical treatment of children with dense bilateral congenital cataracts? Journal of AAPOS, 10:30-6.

- Lifshitz, T., Levy J., Klemperer, I., (2004). ARTISAN® aphakic intraocular lens in children with subluxated crystalline lenses. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 30(9): 1977-87

- Lindsay, R. G., & Chi, J. T. (2010). Contact lens management of infantile aphakia. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 93(1), 3-14. doi:10.1111/j.1444-0938.2009.00447.x

- Nahum, Y., & Spierer, A. (2008). Ocular features of Marfan syndrome: diagnosis and management. The Israel Medical Association Journal: IMAJ, 10(3), 179-181.

- Nemet, A. Y., & Assia, E. I. (2008). Intraocular Lenses in Children. Current Medical Literature: Ophthalmology, 18(1), 1-9.

- Ong, H.S., Subash, M., Adams, G.G. (2012). Spontaneous subluxation of iris-claw aphakic intraocular lens causing complications in two children. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 49, e55-e58.

- Ophtec, (2011). Investigational plan for the Clinical Study of the ARTISAN® Aphakia Lens for the Correction of Aphakia in Children. Study Protocol.

- Por, Y., & Lavin, M. (2005). Techniques of Intraocular Lens Suspension in the Absence of Capsular/Zonular Support. Survey of Ophthalmology, 50(5), 429-462. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.06.010

- Saleh, M., Heitz, A., Bourcier, T., et al. (2013). Sutureless intrascleral intraocular lens implantation after ocular trauma. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery, 39(1), 81-86. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.08.063

- Shah, R., Weikert, M. P., Grannis, C., Hamill, M. B., Kong, L., & Yen, K. G. (2016). Original article: Long-Term Outcomes of Iris-sutured Posterior Chamber Intraocular Lenses in Children. American Journal Of Ophthalmology, 16144-49.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.09.025

- Sminia, M. L., Odenthal, M. T., Wenniger-Prick, L. J., Gortzak-Moorstein, N., & Völker-Dieben, H. J. (2007). Traumatic pediatric cataract: A decade of follow-up after Artisan® aphakia intraocular lens implantation. Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 11(6), 555-558. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.06.015

- Trivedi, R. H., Wilson, J. E., & Facciani, J. (2005). Major article: Secondary Intraocular Lens Implantation for Pediatric Aphakia. Journal Of AAPOS, 9346-352. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.02.010

- Vasavada, V., Vasavada, V. A., Hoffman, R. O., et al. (2008). Intraoperative performance and postoperative outcomes of endocapsular ring implantation in pediatric eyes. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery, 34(9), 1499-1508. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.04.044

- Wilson, M. E., MD. (2018, June 13). Request for Comment for Article on Clinical Trial of Artisan Aphakia in Pediatrics [E-mail interview].

- Wilson, M.E., Trivedi, R.H. (2007). Choice of intraocular lens for pediatric cataract surgery: survey of AAPOS members. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 33(9):1666-1668.

- Xue, K., & Hildebrand, G. D. (2013). Retropupillary ARTISAN® intraocular lens implantation in very young children with aphakia following penetrating eye injuries. Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 17(4), 428-431. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.03.021

- Yamane, S., Sato, S., Maruyama-Inoue, M., & Kadonosono, K. (2017). Flanged Intrascleral Intraocular Lens Fixation with Double-Needle Technique. Ophthalmology, 124(8), 1136-1142. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.03.036

- Yen, K. G., Reddy, A. K., Weikert, M. P., Song, Y., & Hamill, M. B. (2009). Original article: Iris-fixated Posterior Chamber Intraocular Lenses in Children. American Journal Of Ophthalmology, 147121-126. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2008.07.038

- Zhao, Y., Gong, X., Zhu, X., Li, H., Tu, M., Coursey, T. G., & ... Chen, D. (2017). Long-term outcomes of ciliary sulcus versus capsular bag fixation of intraocular lenses in children: An ultrasound biomicroscopy study. Plos ONE, 12(3), 1-13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172979

.jpg)